Lighting design for motion picture can

be controlled by controlling just five factors.

They

are

(1)

Direction/Angle/Position

from where light is coming

(2)

Intensity/Brightness of

light

(3)

Color – is the light

White, blue or yellowish?

(4)

Quality of the shadow –

hard, cut out or soft, fuzzy?

(5)

Texture of light – is

it continuous, drab or patchy?

Below

are given some representations of each.

Light coming from different

directions

Light coming from the same Direction

But of different Color

Light on the character’s face changes in Intensity. Notice

that the Background light is unchanged

Light coming from the same direction and of the same

intensity. But it creates Hard and Soft shadows. Light glitters differently on

the Appy bottle, giving it a different look. That is part of the light’s

texture.

Out of these five

factors, the texture of the light is the most difficult to describe in words,

and even the most difficult to visualize. This is why text books on lighting

avoid this.

Direction/Angle/Position of light

The whole structure

looks like half a wall clock. The five light positions are the basic positions

around the face.

First time

photographers, almost always, place the light next to the camera.

If a single light is

available, that common sense choice is actually the ultimate wrong choice.

Light travels in

straight line. And lighting design is for producing pleasant contrast between

the grounds (Fore, Middle and the Backgrounds) for the story.

To produce contrast,

separate lights are needed for separate grounds.

When light is next to

camera, at 6:00 position of the clock, no contrast can be produced. The same

light would fall on both the human face and the background.

Gerald Millerson, in Lighting for Television & Film, has

described this in great detail.

At 7:30 position of the

light, the face would get a pleasant modelling. On the frame left, the human

face would be lit up.

On the dark side of the face, there would be a patch of

light, Depending on the height of the light, that patch would be above or under

the eye.

When light comes from

the left side of the frame, and such a patch is created under the eye, on the

dark side of the face, it is known as Rembrandt light.

The 17th Century Dutch

painter Rembrandt created such light patches in darkness to build up a

Classical style of human portrait.

When in confusion, it

is wise to set the character light to 7:30 position (or its opposite 4:30).

This direction of lighting seems to be natural for almost all types of moods.

The next basic position

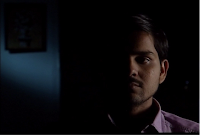

of the light is 9:00. When light comes from that direction, it divides the face

into lit up and fully dark.

A character in

confusion, indecision or dilemma may be lit up like this.

So may be a character

caught up between good and evil, or life and death.

Light position from

6:00 to 9:00, which are near camera positions, are known as the downstage

positions. Specifically 7:30 – 6:00 – 4:30 are known as the downstage ranges.

On the other hand,

upstage lighting creates a lot of contrast. Hence, for very typical night

scenes, or very dark mood, upstage lighting is preferred.

When light comes from

10:30 position, it automatically looks like night. Many people see the white

light as blue, when light comes from this direction. That is an illusion. But,

that happens.

This position of light is known as Kicker. When the Kicker is more like a rim, specially on

long lean faces, it is known like a Rimlight.

Going more upstage, from 10:30 to 11:00, or 11:30,

makes the Kicker more Rimlight for the same face.

When the light is directly behind the character’s face,

the character hides the light from the camera. This happens at 12:00 position.

The character is presented as an outline in the

darkness, for this light position.

If the light is taken to a height above the character’s

head, it produces a halo around the face.

This light is known as backlight, to painters and photographers.

D W Griffith’s Cameraman Billy Bitzer started using

this light for Lilian Gish.

Slowly everyone took to this light, for giving a

glamor look to the hero, or heroine. At the same time, this helped in

separating the character from the background.

Things are pretty same on the other side of the clock.

7:30’s opposite look is produced by 4:30. Similarly, 3:00 divides the face into

halves just like 9:00; and 1:30 produces a Kicker

effect like 10:30.

Position of the light is the most important memory for

a photographer. It is easy to identify the position of the character light in

any other photographer’s, or painter’s, work.

Once a photographer

knows the emotion or mood produced by a certain light position, s/he can make a

note of it. Such notes or diagrams come very handy in reproducing any light

situation very quickly, and precisely.

A Director of

Photography may create such lighting diagrams scene by scene. S/he then hands

them over to the gaffer and the assistant.

They can light up

perfectly using the diagrams as a kind of notation, in the DP’s absence.

That makes work easy

and much quicker.

Half light modified. Note both the eyes are visible.

(To be

Continued)

.jpg)